Why use Linux?

Occasionally, people find out (i.e. I tell them) that I use Linux on my computer.

And then they’re like: “But y tho?”

It’s not clear why anybody would go into the trouble of using Linux. The usual assumption is that Linux is hard to use, and there are some programs that just don’t work on it. It seems that the only possible reason to use Linux would be as a hobby. Maybe Linux users simply have too much free time to waste on getting Linux to work as opposed to normal people who have jobs, families and other more important things to keep them busy.

So how did I end up using Linux and why would anyone else use it?

Linux is pretty cool

I learned about Linux on my first IT job and I therefore assumed that the reason I use Linux is because of my work. I also assumed that other people who use Linux at their job would also be using it on their personal computers.

It turns out, both of these assumptions are false.

In fact, if you look at random web developers or sysadmins, odds are they use Windows or macOS on their work computer even though they might be managing Linux servers. When I worked at Red Hat, where Linux is their main thing, sure, people used Fedora (a Linux distribution) on their work laptops. But many of them would have a Windows computer at home which they used as a gaming and facebook machine. Linux was just their job.

I mentioned I learned Linux on my first job. But I actually didn’t need to learn it for work! The infrastructure I was managing consisted almost exclusively of Windows workstations, connected to Windows Servers. The real reason I learned Linux there was because the two people managing the IT department were passionate about it and they were willing to teach me the basics.

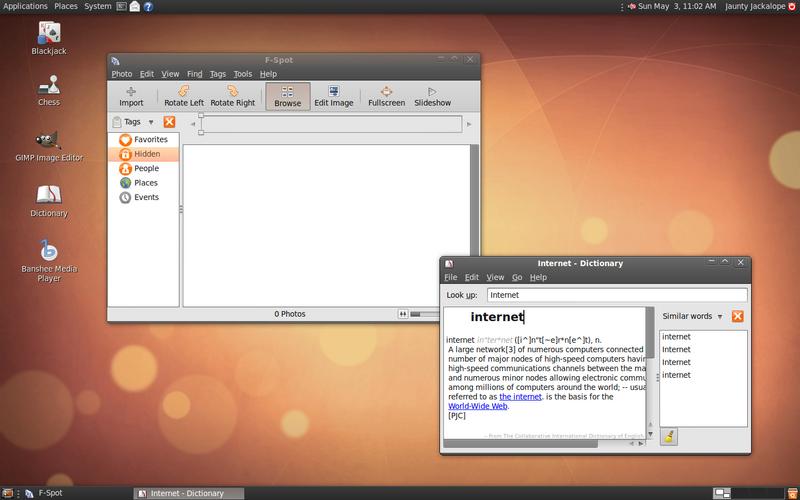

What immediately caught my attention was how it looked. Both the IT guys ran a distribution of Linux on their computers but they looked nothing alike! While everybody else was stuck complaining about the jarring change from Windows XP to Vista, and broke college students like myself would never even think of laying eyes on an Apple computer, here were these IT guys who just happened to have two interfaces that looked and felt different from anything I’d seen before and even from each other.

What I was looking at were called “desktop environments” and while different Linux distributions had a different one installed by default, there was no standard one. There were actually a half-dozen different ones that you could use. You could simply uninstall one and install another. You could even install multiple desktop environments and log into whichever one you felt like when you booted your computer, and as if that wasn’t enough, each one was practically infinitely customizable.

I soon learned that this variety of choice did not stop at the superficial level of the look and feel of the desktop environments. At every level of the system, from how menus are laid-out to how software updates were managed, everything was fully customizable. There were never any licenses you had to buy, you never had to download a mysterious crack.exe from a torrent. In the rare case that your computer crashed or encountered some other fatal error, instead of a blue screen that leaves you guessing as to what the actual problem was, you would get precise error messages telling you exactly what the problem was. You never had to guess or perform a voodoo reboot ritual hoping that the problem will magically go away. Linux told you what the problem was. It was up to you to read, understand, and fix it.

The reboot rituals are worth elaborating on. This is something that people just do and they don’t think twice about it, because they have no other option. If the computer or the mobile device is stuck or not working in some way, you just reboot and hope for the best. On a Windows or a macOS operating system there is a limit on how much of the system is visible to you, so you can’t do any meaningful troubleshooting. Often the reboot works. But you never learn the cause of the problem and you are powerless to prevent it from happening again. Switching to Linux causes a massive shift in mindset. In Linux, unless the computer is completely unresponsive, it is always possible to figure out what is happening without rebooting. Not only that, but rebooting will ruin your chance to figure out the problem. You go from thinking of reboots as a solution to thinking of them as a failure.

All this customizability and control over the system stems from the core element that makes Linux different: Linux is free software. “Free” here does not refer to the price, although free software usually is free in this sense, but rather it refers to “freedom”. The opening paragraph of the wikipedia article on free software explains this succinctly.

Free software (or libre software) is computer software distributed under terms that allow users to run the software for any purpose as well as to study, change, and distribute it and any adapted versions. Free software is a matter of liberty, not price: all users are legally free to do what they want with their copies of a free software (including profiting from them) regardless of how much is paid to obtain the program. Computer programs are deemed “free” if they give end-users (not just the developer) ultimate control over the software and, subsequently, over their devices.

Even if you don’t use Linux, you are using some free software likely without realizing it. Most internet browsers (Brave, Chromium, Firefox) are free software. Even operating systems that aren’t completely free (Android, macOS, iOS) rely heavily on free software components. Most notably, the infrastructure of the Internet is almost all Linux. Whenever you visit a website, or use a mobile app, or interact with the nebulous concept of “the cloud” you are actually connecting to a Linux sever.

Why isn’t everybody using Linux?

All this raises an obvious question: If Linux gives you more freedom and it is capable enough to have taken over the Internet, then why aren’t we all using Linux on our personal computers? This is in part a historical question to which the answer would make this post longer than I would like, so I will rephrase it to consider only the present:

What would prevent you from switching to Linux today?

A candidate answer is that Linux is hard to use. This however is a misconception. Linux on a basic level is as easy to use as Windows or macOS. This is not just a theoretical assumption on my part but a fact I know from personal experience. I have twice now given a computer with Linux installed to two different relatives. One of them was in their twenties and the other in their seventies. They used their Linux computers on a daily basis and they had no issues that they wouldn’t have had with Windows. Even installing it is easy. It used to be that installing Linux in the first place was a feat of computer wizardry, a proper rite of passage. But this has not been the case for over a decade. Today Linux is trivially simple to install, easier even than Windows. This brings us to the next possible issue.

Some hardware is not compatible with Linux. Again, this used to be a much bigger problem in the past. Today the vast majority of personal computers will work just fine with Linux. The real issue here is that in the odd case where a hardware component isn’t supported in Linux, the perceived cost is too high. Nobody wants to pay 1000 euro for a high-end laptop and then find out that the WiFi or the webcam don’t work on Linux. Sure, you can work around it most of the time by using some alternative external device. But objectively, it’s at least an unpleasant experience.

The first, in my view, legitimate obstacle is software compatibility: A lot of important professional software is not written for and not supported on Linux. Consider for example some of the industry leading software a 3D artist will likely use: 3ds Max, Maya, ZBrush, Cinema 4d, OctaneRender, Substance Painter, Blender. Out of these, only the last three are supported on Linux and only Blender is free software. This is actually pretty good. It’s already more Linux support than video editing software. But if you are a professional, it’s just not good enough. If you switch to Linux there are already four important programs that you won’t have access to. You will be missing out on potential competitive advantages that your competitors will have by having access to all the features of all available software in the given industry. In this situation, having a more free computer doesn’t seem worth it if you can’t use it to do your job effectively.

Reliance on specialized professional hardware is, in my estimation, less common than software, but eventually the problem is the same.

But what about gaming?

The situaton is similar. If gaming is your number one priority, you should use Windows. There will be some games that don’t work on Linux. But the reality is that a massive amount of games do work. I do in fact play more games and a wider variety of games than a lot of people, from titles everybody’s heard of, like DOOM and Skyrim, to indie games that nobody has ever heard of, like Velocibox and Devil Daggers. This topic deserves its own post. But for now I’ll just say that video games have always been and will continue to be important to me, and Linux hasn’t changed this.

What it actually means to use Linux

Now, let’s assume that any hardware or software you use for your job is perfectly functional on Linux. There is still one subtle obstacle towards software freedom:

People expect things to “just work”. But the degree to which a thing “just works” is the degree to which it will eventually and inevitably “just break”.

This is true regardless of what operating system you use. A person who installs Ubuntu (a Linux distribution) and never has the curiosity or the patience to learn how it works internally and how all the components of the operating system interact might as well be using Windows or macOS. They will eventually encounter a situation where the computer does something unexpected or just breaks in some way and they will be equally clueless about how to fix it as if they were using Windows. Linux cannot magically make this person more free and empowered in the way they use the computer. It only makes it possible by providing a free and open system. But assuming control of the system in a meaningful way requires intentionality and effort. It is ultimately a deeply personal choice.

Taking control of your computer is also not a choice you can make once and be done with it. It is a lifestyle choice, a continual process, much like a healthy diet, regular exercise, and an intellectually stimulating profession or activity. Maintaining a Linux computer that you actually control in a meaningful way is a life-long process.

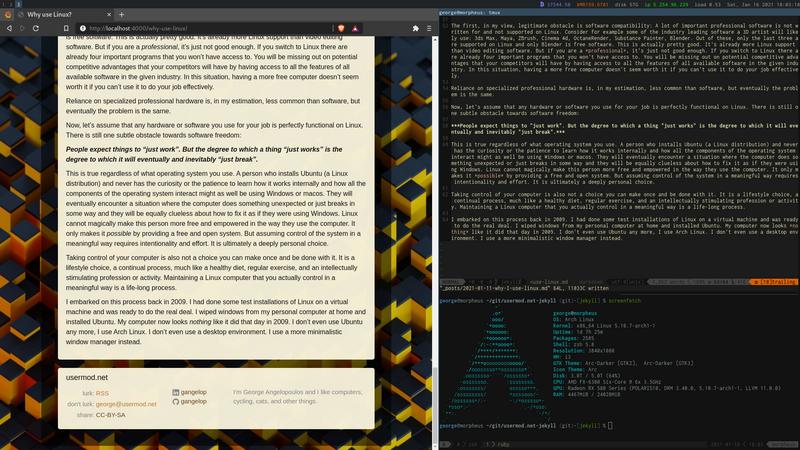

I embarked on this journey back in 2009. I had done some test installations of Linux on a virtual machine and was ready to do the real deal. I wiped Windows from my personal computer at home, I installed Ubuntu, and I’ve never looked back since. Today my computer looks nothing like it did that day in 2009. I don’t use Ubuntu any more, I use Arch Linux. I don’t even use a desktop environment. I use a more minimalistic window manager instead.

Here are some other practical consequences of how I use my computer. Because Arch Linux is a rolling release distribution, I never have to re-install it because of a new release, ever. The last time I re-installed was in 2017 and that was only because I swapped out my spinning hard drive for an SSD. Even then, everything custom about my system I simply copied over to the new installation. But beyond this, when was the last time I actually did a fresh installation? It must have been 2013, when I put together the hardware for this computer. To put it simply, my operating system is fully up to date and I practically haven’t re-installed it in eight years.

I will also never be interrupted by an auto-updater. I download and install updates whenever I choose.

More notably, when some update breaks something I know exactly what caused it, and how to fix it or revert it until it is fixed. Even if a failed update causes the computer to not boot (this has only happened to me once), fixing it is a matter of minutes.

The result of this degree of control is a kind of peace of mind that no Windows or macOS user can ever hope for, no matter how smart they are or how much time they’ve put into learning about their computer. Getting to this level where you have an intimate understanding of how your computer works does require effort. Even IT professionals who work with Linux servers every day won’t automatically know how to manage a Linux desktop system. The opposite is also true: managing your Linux computer will not make you a professional system administrator (although it’s a very good first step). Any way you look at it, there are no shortcuts. Freedom, to use the old cliché, is not free. But it is attainable without having to make it your full-time job.

What is the value of Freedom?

I use Linux because it allows me a greater degree of freedom. This is quite a long post, and if you’ve read this far, chances are there is something about this that resonates with you. In that case, I urge you to consider your freedom. The next time you have to decide to use a piece of software, or buy a computer, or choose a professional career, ask yourself: will using this technology make me more free or less free?

I’m not even suggesting that you should always choose freedom. I certainly don’t. I still rely on some non-free software, I do use a mobile device (in a limited way), and I generally trade some of my autonomy to gain other advantages from the society around me. Freedom is a bit like safety and security. If safety was your number one priority you would never leave the house (although this has become a very popular strategy at the time of writing). Likewise, if freedom was your number one priority, you might choose to live in a cabin in the woods away from civilization (a less popular choice but you’d be surprised at how many people choose it). I am merely suggesting making freedom a consideration. Instead of accepting the ever growing complexity of technology unquestioningly, consider in every situation how it affects your freedom and if it is worth it for you to surrender this freedom for what technology gives you in return.

At the end of the day, nobody else can pay for your freedom. While free software continues to exist thanks to the never ending work of an army of hackers who will never be rich or famous, their collective hacking wizardry cannot liberate you from your digital chains. The mythical “Year of the Linux Desktop” will never come and even if it does, it means nothing. You can only have and maintain freedom analogous to the degree of effort you put into it. The majority of people will always be too busy with things that are more important than their freedom. If contrary to that, you belong to the minority of people who can afford the luxury of using technology on their own terms, use Linux.